- Home

- Rebecca Flowers

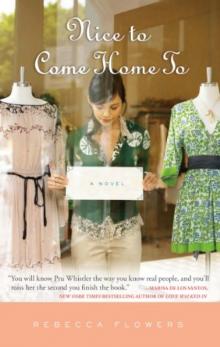

Nice to Come Home To Page 5

Nice to Come Home To Read online

Page 5

“Okay, well, maybe I was sort of keeping him in my back pocket.”

“In your back pocket,” Patsy snorted. “A person isn’t a comb, you know.”

“No,” Pru agreed. “You’d get more use out of a comb.”

Luckily, Patsy laughed at that, and Pru was able to move the conversation along to their upcoming visit. Once or twice a year, Patsy came without Annali, to shop and carouse and do the museums. Pru always enjoyed these visits, although by the end of the weekend, she was ready to see her sister leave. Somehow, when she stayed in Pru’s apartment, Patsy seemed to take up a space many, many times her actual size.

THEY WERE IN THEIR CUSTOMARY PLACES, PRU ON THE couch next to McKay, Bill in his enormous, soft reading chair. She was telling them the same thing she’d told Patsy. They were drinking something Bill made called the Billtini, and passing around a package of Rainbow Chips Deluxe.

“Rudy,” Pru said, widening her eyes. “Good riddance, huh?”

Bill and McKay exchanged looks. Rather, they very purposefully didn’t exchange looks, which was actually more pointed than exchanging looks.

“Okay, what?” Pru said.

McKay put down the remote. “I hate to say it, honey, but you had that coming.”

“What do you mean?”

“Rudy was a sinking ship and he was only going to take you down with him.”

“Come on, that’s not fair. I was giving Rudy a chance. Who says it’s easy? Any good relationship takes work, right? Emotional work?”

Now it was Bill and McKay’s turn to look uncomfortable. They were, after all, men, Pru reflected. They had their limits. Anyway, what did they understand about the struggle between men and women? Lord, they’ve all slept with each other and remained good pals. That tells you right there about the huge canyon between gay and straight relations, she thought.

“Did I mention I saw Gay/Not Gay David?” she said. “Turns out he’s more gay than not. I ran into him in Fresh Fields with a guy, and he didn’t say he was his boyfriend, but you could tell.”

“Were they in the crème fraîche aisle?” said McKay.

“I was going to say ’endive,’” Bill said to McKay, and they beamed at each other.

“So, later, he calls me and asks if it had upset me, seeing them together. Wasn’t that decent of him? And it didn’t bother me, because he really looked happy. So I told him that, and you know what he said? ‘Well, you have a lot more sex being gay.’”

“Oh, hush, you,” McKay said, before Bill could open his mouth to speak. “I don’t care why, but I’m glad Rudy broke up with you. We thought we were going to have to instigate an intervention. You never would have left him, would you?”

“God,” Pru said, sloshing her Billtini on her hand as she put her glass on the table next to the couch. McKay threw a towel at her and she mopped it up. “Was he really that bad?”

“Dear, he was the bad dress of men—a bit too short and clinging to you in all the wrong places.”

“He wasn’t that bad. And you’re not a single woman,” she added. “You don’t know how hard it is.”

“You’re pickier about what you wear than you are about who you sleep with,” said McKay.

“Me? What about you? I can name names, McKay Ettlinger.” Ouch, she thought. He’s right.

Bill stood up. “I think I’ll go make another pitcher.”

She turned back to the TV. Sara Moulton was demonstrating how to debone a chicken. Was Pru the only one who hadn’t seen Rudy for what he really was? Why hadn’t anyone told her? Weak chi . . . a bad dress . . . She felt like she was standing in light, a really nasty, too-bright light, the kind in the dressing rooms at the lesser department stores, where you always find pins and a Kotex strip on the floor.

Rudy wasn’t her dream man, okay. If you’d asked her at the age of six who she’d grow up to marry, she wouldn’t have said a neurotic, culture-obsessed, insecure cartoon producer. But she’d thought him decent enough. Until the TV thing, of course. Obviously, she hadn’t been as clued in as everyone else. David had turned out to be gay . . . Peter had cheated on her . . . Phil had so many problems, she didn’t know where to start. None of these, in her mind, had been casual relationships. She’d been looking for Mr. Prudence Whistler for a long time, and she was beginning to have grave reservations about her judgment. It had served her so well in other areas—she’d blazed her way to this point in life. Why was he abandoning her now?

“Will you guys have a baby with me?” she said, as Bill came out of the kitchen. “I’ll raise it and everything. I just need the sperm. And let’s face it, you two have lots extra floating around here.”

“We’ve talked about that before,” Bill said, refilling her glass. “I’m all for it.”

McKay raised his hand. “And I’m agin’ it.”

Pru sat up. “Really? Did you talk about me as the birth mother?”

“Of course,” said McKay. “Of all the women we don’t want to sleep with, babe, you’re number one.”

“But you wouldn’t have to do all the caregiving yourself,” Bill said. “We’d want to be involved fathers.”

“You know,” said McKay. “We’d want to see it before you bring it up to bed at night. Briefly.”

“By ‘it’ he means ‘him or her,’ ” added Bill.

LATER, IN THE STRIPED COTTON PAJAMAS MC KAY HAD given her to sleep in, safe and cozy under the seersucker bedspread, she wondered, Why not? McKay and Bill would be great fathers, attentive and gentle and fun. She’d be the mother and housewife. She’d remember to bring McKay’s empty glasses of Diet Squirt back to the kitchen, and have dinner waiting for them every night. They’d show up at PTA meetings together and chaperone the prom as a threesome. They would grow old together, reading the kids’ letters out loud to one another, trading quips and playing board games.

The next day, after breakfast, Pru and McKay drove to the D.C. Humane Society. It was in a strip mall in one of the worst neighborhoods she’d ever seen. The entire block looked like it had been hit by a bomb. There were only two other storefronts occupied: what looked to be a Mylar balloon shop, and something called Deondre Dress. Inside the animal shelter, a handful of dogs kept up a constant racket. Others lay about despondently in the heat. It was about a thousand degrees inside, and smelled of thick, warm pet smells. She couldn’t stand the naked need of the puppies in what was called the Puppy Playground, and quickly left McKay to wander around.

She found herself in the Cat Condo. It was a sad, lackluster place. The few people who’d come to look at felines were all in the Kitten Kastle, oohing and ahhing over the tiny, mewling babies. Here, the elderly cats were left to nap, undisturbed. A few regarded her with distant, cool eyes. She was about to go back and find McKay when the sight of a cat in its cage stopped her. It was a huge tabby, absolutely massive. It had a notch in one ear, and it sat back on its haunches, sleeping, like a bum on the street. It looked exactly like Rudy’s cat, the cat that had menaced her the one and only night she’d slept over at his place. She took off her hat and her sunglass clip, to get a better look at the cat. He was so large that there almost wasn’t any room for him in the cage. Pru couldn’t remember his name, so she said, “Rudy?” The cat’s eyes opened. They were the same amber as Rudy’s cat’s eyes, and they wore the same utterly blank expression with which they’d always regarded her. No doubt about it; this was Rudy Fisch’s cat.

But what on earth was it doing here? Rudy was ridiculously devoted to the beast. If he was spending the night at Pru’s, he’d stop at home after work to feed the cat and play with it. He did this even though it took him an hour out of the way. She’d thought of it as a good sign, when they’d first met, and, in fact, HAS CAT was listed in the pro column of the Rudy list. It meant he could care for something. Of course, the morning after it spat at her, HAS CAT appeared on the con side, too, thereby canceling itself out.

McKay wasn’t in the Puppy Playground. She found him in the Doggie Den, kneeling in fr

ont of what looked to be a dirty dust mop on four legs. Like the Cat Condo, it was much quieter here, almost eerily so. The cage behind them was opened, and McKay was letting the dust mop lick his hand.

“What are you doing?” she said.

“Nothing,” he said, mock innocently.

“I think I saw Rudy’s cat, in there. In fact, I’m sure it was Rudy’s cat. In the Cat Condo.”

“Rudy Fisch? What’s his cat doing in the Cat Condo?”

“I don’t know. Playing shuffleboard?”

“Do you think Rudy dumped him?”

“I wouldn’t have thought so, but I can’t imagine how else he’d get here. I’ve never seen the cat leave the couch, much less the apartment. I guess maybe he did. He’s in something of a dumping phase, isn’t he?”

“So, what did you do about it?” McKay said.

“About Rudy’s cat? Nothing.”

McKay looked genuinely appalled. “Prudence Whistler. You just left that poor thing there?”

“I didn’t dump the cat. Hell, it never even lived with me. Why is this my problem?”

“I don’t know, but it is.”

“I’m not really a pet person.”

“So? Just call Rudy and tell him it’s there. Maybe he doesn’t even know.”

“No,” she said firmly. “No way. I wouldn’t call Rudy if I’d found his mother in a cage at the Humane Society. Although, frankly, it would be easier to understand.”

McKay shrugged. “All right,” he said. “But this is on your head. Look at her eyes,” he said, raising the dog’s face so Pru could see. “Aren’t they intelligent? Huskies are supposed to be very smart dogs.”

The husky’s fur was matted and gray. She performed no tricks, emitted no grunts, exhaled no sweet warm puppy breath. Her teeth were yellow. She sat there and panted, wetly. Leave it to McKay to choose the dog that looked most ready to keel over. He really was a ridiculously soft touch.

“You’re not getting attached, are you?”

“Oh, no. Of course not.”

“I promised Bill . . .”

“Just relax. There’s something going on between me and this here girl.”

McKay stood and moved a short distance away, then snapped his fingers. Slowly, the dog stood and obediently dragged herself over to him, then sat at his feet, swaying a little.

“Look at that,” McKay said, delighted. “She already obeys me.”

“Stop,” Pru said, dryly, automatically. “You are not going home with this dog.”

“Don’t be silly,” said McKay. “They kill animals that are left here, you know. I can’t do that to poor Oxo.”

“What’s an Oxo?”

“Her name!”

Pru looked at the tag on the cage. “It says here ’Debbie.’”

“Well, now it’s Oxo.”

“You’re naming her after a can opener?”

McKay bent low to the dog, running his hand over her head and cooing, “You’re coming with me, aren’t you, girl? Aren’t you, girl? Yes, you are! Yes, you are!”

Five

On Monday morning she sat at the little desk in her living room, chewing on her pen and staring out the window. She’d made herself change out of her pajamas, into her comfiest pair of Lucky jeans and a peasant blouse. She’d even made herself put on shoes, the ones that laced up her legs, under the jeans. She thought she looked very work-at-homey. It was cooler than it had been in weeks, but still warm enough that she kept the windows open.

She used to love this time of year, back-to-school time. She loved the smell of sharpened pencils, the clean sheets of paper in her three-ring binder. The night before the first day of school, she and Patsy would sit at the kitchen table, folding book covers out of brown paper bags and decorating them with magic markers. Everything would be new and shiny and ready for the next day. She’d have picked out her outfit for school before she went to sleep.

But now she was feeling restless and antsy. Since she’d lost her job she’d had the odd sense of carrying around a big bucket of water. The bucket was filled to the brim and almost too heavy to lift, and she couldn’t figure out where to put it down. Ordinarily she would have left it next to her desk, at work. Or she’d have given it to Rudy. But now she just had to keep slogging that bucket around with her, from one place to another, everywhere she went.

On the drive home from the Humane Society, while McKay talked to the happy, loudly panting dog in the rearview mirror, she’d come up with a better plan than finding another full-time job: consulting. She liked the dignified sound of it. She’d be her own boss, and she could do almost all her work out of her apartment. Maybe she wasn’t cut out for an office job after all. It was true, she missed her old desk, with its neatly arranged surface. She missed her commute, across the bridge to Woodley Park Metro station. She missed the structure the job had given her, the sense of purpose. And of course, some of her business clothes. Not the tired old interview suit she’d worn to the conference last week, but the pieces she thought of as “business sexy,” clingy silk wrap dresses and Italian high heels and dozens of leather commuter bags. But she was getting used to being at home. She was comfortable here. She liked being out in her neighborhood in the daytime, able to see what everyone was doing.

And consulting would let her expand her horizons. So, fine, she had no real passion for fund-raising. Her passion. She’d never thought of herself as passionate. She chewed her pen and looked around at the drab, nothing-colored walls of her living room. The corner where the TV had been was empty and cobwebby. She wished she was back at McKay and Bill’s, lying on the couch and watching cable TV cooking shows. That, she could do all day. I have a passion for wasting time.

She couldn’t work in a room with such a dismal corner. She jumped up and grabbed a feather duster and began cleaning. Somehow the walls had gotten all scuffed up, probably when Rudy had hoisted the massive television up on its stand. Really, she should paint the living room. Preferably before Patsy came, on Friday. Her sister was very sensitive to her surroundings, and would surely have something to say about it, such as How like you, Pru, to live with nothing-colored walls.

Probably she should take the week and do the whole apartment before buckling down to work, she thought while walking through the rooms. With e-mail now, everything happened so quickly. She wouldn’t want to start painting only to get a job offer the very next day. Maybe she’d even get a break on the rent, for the new paint.

She grabbed her jacket and purse and headed out to the paint store on Seventeenth Street. That could be part of her consulting work! She could hire herself out to the other condo owners in the building, painting, spackling, doing whatever was needed. She could be a sort of Jill-of-all-trades, getting by on her sweat and her labor. Then she remembered that laborers worked hard, and she wasn’t sure she would like that very much.

Definitely, though, she’d paint the apartment, for Patsy.

SHE GOT RIGHT TO WORK. SHE WAS SO EXCITED TO SEE the pale lavender she’d chosen for the living room actually up on the walls that she didn’t even bother to prime them first. When McKay came to inspect her work, later, he scolded her for that. But then he helped her choose a soft sage green for the bedroom, and insisted on hand-mixing it himself. She spent the whole week painting. The days flew by. She loved doing the cutting-in around the trim and the ceiling, in particular. It required concentration and attention and she had plenty of that. She’d gotten an audiobook called The Voice of Winston Churchill, and she listened to it while she worked.

Never give in. Never give in. Never, never, never, never—in nothing, great or small, large or petty—never give in except to convictions of honour and good sense. Never yield to force; never yield to the apparently overwhelming might of the enemy.

She didn’t give in, to boredom, to frustration, to the dizziness in her head when she was forced to stand on the top step of the ladder nearly upside down, to reach the molding. She didn’t give in to the stubborn patches of drywall tha

t refused to absorb the paint. She didn’t give in to her impulses (many, many of them) to put the paintbrush down and go have a drink with McKay. While listening to Churchill, painting the walls of her apartment felt inspired, absorbingly religious. Sounds from the street below came in through her open windows. “Hey, chollo!” “I’m like, darling, we’re not going there, are we?” “Christopher Anthony, you get your butt back here this minute!”

She finished the last wall of the bedroom on Thursday afternoon. She cleaned the brushes and the paint trays and brought the ladder back to the basement. She put all the furniture back and swept the floor and looked around. The colors made her feel better. The colors, and Churchill’s speeches. Not happy, but better.

It was four o’clock in the afternoon. A time she hated. A time for nothing. The sun was setting, at an angle she found painful. It wasn’t time to eat. She didn’t feel like taking a walk. McKay was at work, all her friends were at work. It was a Thursday—not a party night, not a laundry night. She sat on her couch, looking at her newly painted walls, and feeling, slowly, the return of the bucket of water she’d been carrying.

PATSY WAS WEARING ONE OF HER OLD ARMY COATS AND a pair of white hairy yak boots, when Pru picked her up at National Airport the following day. She had a new piercing, in her right nostril, and her long, dirty-blond hair was piled on top of her head. It looked like it might have included some dread-locks. They went straight to Chinatown, stopping at Pru’s only long enough to drop off Patsy’s knapsack. Chinatown was Patsy’s favorite place to shop when she was in D.C. She liked the cheap straw hats and silk shirts and combs for her hair, anything that looked sparkly and pretty and not made in Ohio but, Pru couldn’t help pointing out, in some third-world sweatshop.

On the Metro, Patsy said, “What am I supposed to be feeling here? Grief? Relief? I never know where to stand with you.” She pulled back so she could look at Pru. Patsy was actually the taller one, although younger by four years. The fact that she mistakenly got pregnant out of wedlock added to Pru’s impression of Patsy being even younger. But now that Patsy was a mother, she felt entitled to seize the role of the older sister. She acted bossy and knowledgeable. Pru found it quite irritating, and wondered if this was how Patsy had felt, growing up.

Nice to Come Home To

Nice to Come Home To