- Home

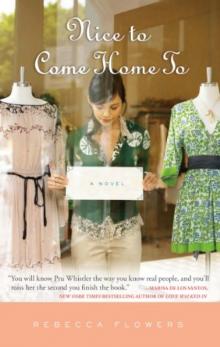

- Rebecca Flowers

Nice to Come Home To

Nice to Come Home To Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Acknowledgements

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3,

Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) • Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand,

London WC2R 0RL, England • Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2,

Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) • Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell

Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

• Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi-

110 017, India • Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) • Penguin Books (South Africa)

(Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Copyright © 2008 by Rebecca Flowers

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned,

or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do

not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation

of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Published simultaneously in Canada

The author acknowledges permission to reprint lyrics from

“Thunder Road” by Bruce Springsteen. Copyright © 1975 Bruce Springsteen,

renewed © 2003 Bruce Springsteen (ASCAP). .

International copyright secured. All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Flowers, Rebecca.

Nice to come home to / Rebecca Flowers.

p. cm.

eISBN : 978-1-4406-3380-5

1. Single women—Fiction. 2. Sisters—Fiction. 3. Family—Fiction.

4. Adams Morgan (Washington, D.C.)—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3606.L686N

813’.6—dc22

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

http://us.penguingroup.com

For Andrew,

as in all things

One

Prudence Whistler was at a conference at the Sheraton on Connecticut Avenue when she saw the woman she was supposed to be by now.

Pru was trying to persuade the executive director of an important nonprofit to give her a job. She’d followed him out of the Gerald R. Ford Room, where he’d been giving a talk called “Follow the Money!” The conference (“A Passion for Mission!”) was for fund-raising professionals, and as if to compensate for the dullness of the proceedings, everything ended with an exclamation point.

As soon as he’d seen that an attractive woman wanted something from him, the executive director scooted right in close to Pru, one hand sliding along her back. He’d pushed a fleshy ear practically into her mouth, although the hallway was empty. Pru tried not to stiffen. She needed a job. She’d been without one for ten days now, the longest she could ever remember. Soon it would be two weeks. Two weeks, with no job. She took a deep breath. He was way inside her personal bubble. He was, in fact, looking down her personal bubble’s shirt.

The executive director began fingering the back of her bra strap while Pru blathered on, hardly aware of what she was saying. She still wasn’t used to the game. She had hoped that the nonprofit world would be a decent place, full of well-meaning people working shoulder to shoulder for a noble cause. Like how she had first envisioned a Communist society: men and women working together as equals, in matching unisex jumpsuits and caps. She’d had a lot of illusions like that when she’d gotten her first nonprofit job, more than ten years ago, after graduate school. But she’d found that this world, too, had its share of huge egos, inflated salaries, and horrendous working conditions. And also little power games, like this one.

“Prudence,” he said, interrupting her spiel. He bent to squint at the small, neat print on the name tag pinned to her chest. “Is that your handwriting? Am I supposed to be able to read that?”

She was barely able to refrain from sighing audibly. She looked at him, trying to find something likable. She tried to imagine him as a younger man. He must miss those days, she thought, high school or maybe college, back when girls would flirt with him because he was cute and played football. Or no; the girls never flirted with him, until he became the executive director of a $20 million-a-year international relief agency. He wasn’t super-attractive, but he dressed nicely and his shoes (tasseled loafers—Jesus) were polished. She approved of that, anyway.

“I don’t know, maybe you need glasses,” she said. It was a pathetic attempt, but he brightened. She was being cheeky with him, a known big shot.

“Hey,” he said. The hand on her back now gave her upper arm a friendly squeeze. “Are you calling me old? I bet I’m not so much older than you. What are you, thirty-five, thirty-six?”

The fake smile she’d been holding slid from her face. She could feel angry tears stinging her eyes. Was he kidding?

“Uh-oh,” he said, laughing. Had he even bothered to shave off five years, as politeness demanded? Gripping her arm more tightly, he said, “You don’t look it, I swear. Listen, I was going to go somewhere better than this for lunch. Come with me. My treat. Come on, let me make it up to you.”

He was so close she could feel his breath on the side of her face. That was when she looked up and saw a woman who could be her twin. Tall and broad-shouldered, like Pru, the woman was striding toward her from the other end of the hotel lobby. For a moment, Pru thought she’d caught her own reflection in one of the hotel’s ornate gilt mirrors. Then she saw that the woman was enormously pregnant, and accompanied by two little girls marching side by side in bathing suits and the same dime-store daisy-toed flip-flops that Pru and her sister, Patsy, used to wear. Following close behind the woman, carrying pool toys and towels, came a nice-looking husband in a Princeton T-shirt.

Normally Pru would take one look at such a woman and dismiss her as one of those pampered, sheltered, stay-at-home types, whose only burdens were a huge diamond on her finger and a fat fashion magazine under one arm. She would have remembered her clean little apartment in the city, the comfortable arrangement she had with her attentive boyfriend, all the time she had to read books and eat

at restaurants and watch movies. She would remember her friend Fiona, who complained constantly about the demands of motherhood. Or her sister, who was raising a daughter by herself on her schoolteacher’s tiny salary. And she would have felt grateful for her freedom, glad she and Rudy were waiting until the time was right to get married and have kids.

But today was different. It might have been the letch she was trying to shmooze, breathing down her shirt. Or the fact that, in four more days, it would be exactly two weeks since she’d lost the job that was supposed to advance her career and let her buy a four-bedroom fixer-upper in Cleveland Park and take a nice long maternity leave in the not too distant future. Or maybe it was because Rudy had been out of town all week, at a conference for public television executives in Chicago, where he was so busy they’d only had the briefest of conversations, at night, before she went to sleep.

Or maybe it was because, as a child, Prudence had loved family hotel vacations. All of them together, in one room, with real silver on the room service tray, and clean sheets every night. Running through the corridors with Patsy, and riding up and down in the elevators. She’d always wanted to live in a hotel, like Eloise.

Whatever the cause, suddenly all her plans seemed pathetic and narrow. Next to the golden, fructive mother-ship before her, Pru felt like both a withered old spinster and a child. She felt hard and tired out, in her severe worsted wool suit, the sad little scarf she’d tied around her neck to brighten her face announcing her desperation. The woman before her, coming toward her like her own future—there was a woman who knew her place in the universe. She would go up to her hotel room tonight, after dinner, and tuck in those little girls, whose arms would linger around her neck for a moment, when she kissed their foreheads. They would smell her perfume, and she would smell their no-more-tears shampoo, and faintly, the chlorine left over from their swim. Pru could imagine it, all of it, entirely, all of a sudden. Her fingertips could practically feel the girls’ silky hair against the pillowcase. This was a woman who had what a job would never give you. She was loved, and she would never grow old alone.

As Pru watched, transfixed and pained at the vision of herself as wife and mother, the little family moved through a ray of sunlight coming in through the hotel’s atrium, so they were lit up, like angels.

Pru felt a grip of fear in her gut. Grow old alone! She’d forgotten about that! She’d been so busy at work that she’d forgotten about growing old—possibly even dying—alone. It wasn’t so far off now. And people in their thirties got horrible diseases, all the time. What would her 401(k) do for her when she was lying in bed, immobilized by terminal cancer? She could scarcely breathe for the thought of it.

The executive director had turned around to see what had attracted Pru’s attention. The sight of the blond, angelic-looking family perhaps reminded him of his own wife and children, because he quickly straightened up and gave Pru a fatherly pat on the back. “Actually, I’m just going to grab a sandwich and eat at my desk,” he said. “Good meeting you.” And before Pru could recover her composure long enough to give him her business card or even her last name, he was gone.

Behind her, the doors to the Gerald R. Ford Room burst open, and out came the rest of the conference attendees. They streamed from the room and around Pru, heading toward another room that had been set up for lunch. A tributary to the stream headed outside for a cigarette, and another to the bathrooms, while Pru stood rooted to the spot like an old dead tree, blinking in bewilderment, wondering how she’d forgotten to have a husband and children by this point in her life.

WELL, IT WASN’T LIKE SHE’D FORGOTTEN, EXACTLY.

In the back of her Daytimer, in fact, behind a list of her boyfriend Rudy’s faults (or so he called them; she called them, more peaceably, his “pros and cons”) and a list of clothes she wanted to buy, was her five-year plan. It had been unfolded and refolded so many times that the edges were soft, and nearly came apart in her hands, like some kind of historical document.

Pru was a believer in lists and plans. She’d made her first five-year plan when she was nine. It had included becoming an astronaut, a schoolteacher, and the mother of four children (two boys and two girls) before turning twenty.

She’d come up with her current, more realistic plan in college. Married with children by 29, she read. She remembered making the list in her dorm room, cold winter light pouring in through the window by the desk where she sat writing, a pot of tea steeping nearby. The 29 had since been crossed out, and replaced with 30. Then 32, then 34. And then she’d stopped bothering to update it altogether.

She always thought she’d have a lot of kids. She thought of herself as a maternal person, sensible and loving. She’d played with dolls long past the time when her friends had turned to other things—like Bonne Belle Lip Smackers and Tiger Beat magazine—and she was strict but loving with her stuffed animals, each of whom got a turn once a week sleeping next to her on the pillow. Even now, she felt the cravings on the inside of her arms, and somewhere along the base of her jaw, almost like salivary glands, when she held small babies. And she doted on her niece Annali, with her heart-shaped face, her cap of blond curls—but of course, who wouldn’t, with a kid like that?

And Rudy was right there, too. He liked kids. His own childhood was a source of immeasurable, endlessly recollectable pleasure for him. He loved comic books, cartoons, and Quisp cereal (which he’d recently given up in favor of low-calorie twigs of bran). The fact that he wanted children, too, had been the most heavily weighted item on her pros-and-cons list (she’d given it five full points). And still, she hadn’t been able to pull the trigger. It had now been two months since the last time they’d talked about getting married. Rudy had grown strangely silent on the subject.

She couldn’t say why she kept putting him off. She told herself it was because they had a good thing going, so why ruin it? They could be together when they wanted to be, and each had an apartment to retreat to for what they called “me time.” Pru had found that, dating Rudy, she needed a lot of “me time.”

Being with Rudy could be exhausting. He practically had an advanced degree in pop culture, with an emphasis on his own childhood, and he needed a lot of attention, as the funny often do. Sometimes the apartment seemed so full of Rudy—of Rudy’s needs, of Rudy’s problems, of Rudy’s therapy, his little jokes and his dirty socks.

A few months ago, she’d tried to talk to him about taking a break from seeing so much of each other. She had begun to wonder whether they had really chosen to be together or just fallen into the habit. But then Rudy went through a bad patch. He was promoted from animator to producer, which seemed at the time like a good thing; but then the pressure that came with assuming nominal control of the ragtag group of smart, neurotic comedy nerds he used to belong to made him anxious and depressed. It didn’t seem right to leave him, just then.

And then the tables turned, and now she needed him. She’d never been fired before. Not even anything close to that. Right away, she’d thrown herself into the work of finding another job, as though that would erase what had just happened. She found herself missing Rudy, counting the hours until he would be home from work. She wasn’t entirely comfortable with that. She wanted to turn the tables back again, so they faced in the proper direction.

In the darkness of the lunchtime session, she gathered up her things and slipped out before the PowerPoint presentation was over. She couldn’t wait to get home and rip off her business suit. She wanted to shove it into the back of the closet and never see it again; but of course Pru would never really do that with wool crepe.

She was wasting her time at the conference. This wasn’t the direction her future was taking her; she was absolutely certain of that. She had another vision of herself, this time sitting on a primary-colored carpet, playing quietly with a baby. She would wear those capri khakis, maybe, with layered T-shirts, and her cork-wedgie sandals.

Oh, this in-betweenness—how she hated it! They needed to fish or cut

bait, as her mother would say. What did she need, big fat red arrows pointing the way? It couldn’t have been an accident, seeing in that pregnant woman a vision of her future self. What better time, really, than now, to get married and have children? Didn’t people take sabbaticals from their jobs, to write books or do research or whatever? Why not a sabbatical to start a family?

On her way out of the hotel, she happened to spot the little family again. The girls were playing at the koi pond in the lobby. This time, Pru got close enough to the woman so that she could say, “What sweet little girls you have.”

“Thanks.” The woman beamed. Then she rolled her eyes. They were the same gray-blue as Pru’s, under the same straight brows. “Until it’s time to go to bed. That’s when they getcha.”

Pru nodded. That was just what she would have said, too—the obvious pride, followed by a touch of humility. Just right, for a woman her age.

Two

“Rudy Fisch? God, why?”

McKay had a way of saying Rudy’s name that made Pru picture a fat, glaring trout.

McKay didn’t like Rudy because they had the same sense of humor, and, he said, because Rudy was an asshole.

Pru and McKay were having a beer at the bar under the souvlaki place next to Pru’s apartment, on the Friday Rudy was due home. She was meeting him in a few hours, outside the Film Institute. She’d spent the days following her encounter with her future self making plans. (How she loved planning! Always much better than doing.) She found out that to book a wedding venue in D.C., you needed at least a year’s notice. She was stunned at the cost—most places asked for $10,000 just to rent them for the day. She was toying now with the idea of a justice-of-the-peace wedding, followed by dinner at one of the nice restaurants in Georgetown for everyone: her mother, sister, and her niece; Rudy’s parents (no getting out of that, unfortunately); McKay and Bill, of course; and her best friend Kate McCabe. In her Daytimer now was a newspaper ad for two-bedroom apartments in a new building in Columbia Heights, a not-too-scary but affordable neighborhood near her own neighborhood, Adams-Morgan. She’d love to stay in Adams-Morgan, but it had become so gentrified that she and Rudy would never be able to buy a place there now. There was also a new tab, marked “Stroller Research.” She’d even put in a bid on a vintage double Peg Perego she’d found on eBay, currently a steal at $95.50. Sure, she didn’t actually have kids, and it would take up half of her living room. The bid was also reckless, in light of the fact that she was trying to cut expenses wherever she could (she’d already canceled her membership at the upscale Y on Rhode Island Avenue, and sworn off cabs). But she couldn’t resist. Maybe the stroller would double in the meantime as a plant stand or something. Doing these things made Pru feel less lonely. In fact, this was the happiest she’d been in months.

Nice to Come Home To

Nice to Come Home To